Key Takeaways

- The oil and gas value chain links exploration, production, transportation, and refining into one continuous system that moves hydrocarbons from the subsurface to end-use products. Whether you're assessing energy investments or learning the basics of the industry, understanding how each segment works and how they interact provides a strong foundation.

Introduction

The upstream oil and gas value chain is the starting point of a global system that moves hydrocarbons from deep reservoirs to the fuels, plastics, and chemicals used every day. Most people encounter gasoline or LPG at the end of that chain, but the real story begins far earlier with seismic surveys, drilling crews, complex pipeline networks, and refineries that turn raw hydrocarbons into usable products.

This guide walks through each major segment; upstream, midstream, and downstream. It explains how they interact. Investors, students, and professionals entering energy markets often find it easier to understand the industry by seeing how the entire system fits together rather than studying each segment in isolation.

Upstream: Exploration and Production (E&P)

The upstream oil and gas value chain is responsible for locating hydrocarbons, drilling wells, and managing upstream oil and gas production of crude oil and natural gas. These operations can be onshore (Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar Field, West Texas’ Permian Basin) or offshore (Brazil’s pre-salt fields, the North Sea, Gulf of Mexico).

Key Activities in Upstream

Exploration

Companies invest heavily in identifying where hydrocarbon reservoirs may exist.

Geological surveys: rock sampling, structural mapping

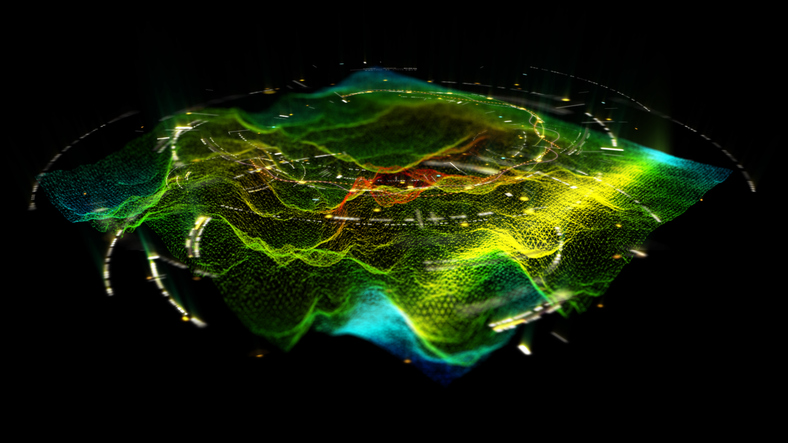

Seismic imaging: 2D/3D/4D seismic data to visualize subsurface layers

Reservoir evaluation: estimating recoverable volumes

Lease acquisition: securing drilling rights

Environmental and regulatory approvals

Example:

A company planning to drill in the Guyana–Suriname Basin typically spends months acquiring seismic data, then uses reservoir modeling software to estimate potential recoverable reserves before committing to a multi-million-dollar well.

Drilling and Well Construction

Once exploration indicates commercial potential, the modern oil drilling process begins, translating subsurface data into safe and productive wells.

Drilling rigs are mobilized (land rigs, jack-ups, semi-subs, drillships).

Companies install casing, tubing, and wellheads.

Engineers design the well path (vertical, deviated, horizontal).

Service companies supply drilling mud, cement, and wireline logging services.

Drilling is one of the most capital-intensive parts of the entire value chain. According to cost breakdowns from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA, 2023), well construction can account for 40–60% of total upstream spending in unconventional wells.

Production Operations

After completing the well:

Hydrocarbons flow to the surface via natural pressure or artificial lift.

Fluids enter separators to remove water, sand, and contaminants.

Gas is treated or flared (depending on regulation and infrastructure).

Crude is stored temporarily before midstream takeover.

Production lifecycles can range from 3 years in shale wells to 20–40 years in conventional offshore fields.

Well Abandonment

When a well is no longer economical:

Operators plug the wellbore with cement

Remove surface equipment

Restore the site

File regulatory documentation

Abandonment is essential for environmental compliance and is often tightly regulated (e.g., BSEE’s offshore rules in the U.S.).

Midstream: Transportation, Storage & Processing

Midstream sits between production and refining. It basically involves transportation, storage, and processing from the upstream. It moves, stores, and prepares hydrocarbons for further processing.

What Midstream Companies Handle

Pipelines: crude, natural gas, NGL, and products

Tanker transport: VLCCs, LNG carriers

Trucking and rail systems (common in North America)

Gas processing plants

NGL fractionation units

Midstream Processing Output

Raw natural gas from upstream cannot go directly to the consumer. It must be processed into:

Pipeline-quality gas (primarily methane)

NGLs: ethane, propane, butane

LPG: propane–butane blends

LNG: chilled to –162°C for export

CNG: compressed methane for fleets and storage

These quality standards are strict. Contract specs often list composition, density, water content, sulfur, BTU value, and vapor pressure.

For crude oil, midstream focuses on:

Stabilization

Storage in tank farms

Blending to meet refinery feedstock needs

Transport via pipeline or tanker

Example:

Crude produced in the Permian Basin often travels hundreds of miles by pipeline to refineries in Houston or Corpus Christi. Differences in sulfur content or API gravity may require blending before reaching the refinery.

Downstream: Refining and Petrochemicals

Downstream converts raw hydrocarbons into usable products. This includes refineries, gas separation plants, petrochemical plants, and chemical manufacturing.

Refining

Refineries process crude using distillation, catalytic cracking, hydrotreating, and reforming units.

Main Products Include:

Gasoline

Diesel

Jet fuel

Kerosene

Naphtha

Lubricants

Asphalt/bitumen

Bunker fuel

Petrochemical feedstocks

Refineries carefully adjust their crude slate, the mix of crude types they run, to optimize margin. A refinery in Singapore might switch between Middle Eastern medium-sour crude and U.S. light-sweet crude depending on freight rates and price spreads.

Petrochemicals

The petrochemical value chain transforms feedstocks such as ethylene, propylene, and benzene into products including:

Polyethylene

Polypropylene

Styrene

Synthetic rubber

Solvents and industrial chemicals

Ethylene can be produced from:

Ethane (from natural gas processing)

Naphtha (from refineries)

This is why petrochemicals link tightly with both midstream and downstream segments.

The Ground-to-Consumer Path

The oil and gas value chain works as a continuous system, moving energy from the subsurface to end users.

A simple way to visualize the value chain:

Upstream: Find it → Drill it → Produce it

Upstream companies locate hydrocarbon resources, drill wells, and extract oil and gas. Decisions made at this stage affect supply volume, quality, and production costs across the entire industry.

Midstream: Move it → Store it → Process it

Midstream operations transport crude oil and natural gas through pipelines, tankers, rail, or trucks. Storage terminals and processing facilities manage volume, quality, and reliability before delivery to refineries or gas markets.

Downstream: Refine it → Convert it → Deliver it

Downstream facilities refine crude oil into fuels and petrochemical products. These products are then distributed to industries, power plants, and consumers through retail and wholesale networks.

Each segment depends on specialized companies, regulatory oversight, and market conditions. Disruptions such as drilling delays, pipeline constraints, or refinery shutdowns can interrupt supply, increase costs, and affect energy prices across regions.

A well-coordinated value chain is essential for reliable energy supply and market stability.

Who Operates Each Segment of the Value Chain

Different types of companies specialize in different parts of the oil and gas value chain, reflecting varying risk profiles and capital requirements.

Upstream operators include national oil companies (NOCs), international oil companies (IOCs), and independent producers. These firms focus on exploration, drilling, and production and carry the highest geological and price risk.

Midstream companies specialize in pipelines, storage terminals, gas processing plants, and export facilities. Their business models often rely on long-term contracts rather than commodity prices.

Downstream players include refiners, petrochemical producers, fuel marketers, and retailers. These companies convert hydrocarbons into finished products and sell them to end users.

This specialization allows firms to concentrate expertise and manage risk more effectively.

Capital Intensity and Risk Across the Value Chain

Each segment of the value chain carries a distinct cost structure and risk profile.

Upstream is the most capital-intensive and risky. Exploration and production wells may not succeed, and revenues fluctuate directly with oil and gas prices.

Midstream involves large upfront infrastructure investments but typically delivers more stable cash flows through regulated tariffs or fee-based contracts.

Downstream margins depend on refinery utilization, feedstock costs, and demand for refined products, making profitability cyclical.

Understanding these differences helps explain why investors allocate capital differently across segments.

Regulatory and Environmental Oversight Across the Chain

Oil and gas operations are heavily regulated, but oversight varies by segment.

Upstream regulation covers land access, drilling permits, emissions, water use, and well abandonment. Environmental compliance is enforced throughout the life of a field.

Midstream regulation focuses on pipeline safety, transportation tariffs, storage standards, and cross-border trade approvals.

Downstream regulation includes fuel quality standards, emissions limits, occupational safety, and environmental reporting.

Strong regulatory frameworks aim to protect public safety while ensuring reliable energy supply.

The Role of Technology and Digitalization

Technology underpins efficiency, safety, and cost control across the entire value chain.

In upstream, automation, AI, seismic modeling, and digital twins improve reservoir understanding and drilling performance.

In midstream, SCADA systems, sensors, and predictive maintenance improve pipeline reliability and prevent outages.

In downstream, advanced process control and refinery optimization software maximize margins and reduce energy intensity.

Digital integration enables faster decision-making and improves coordination between segments.

Why Understanding the Value Chain Matters

For investors, analysts, and students, the oil and gas value chain provides a practical framework for understanding how the industry really works.

Identifies risks and bottlenecks

Each segment faces different risks. Upstream is exposed to exploration risk and price volatility, midstream to infrastructure and regulatory risk, and downstream to demand cycles and operational efficiency.Explains the impact of geopolitical events

Conflicts, sanctions, or policy changes often affect upstream supply first, then ripple through pipelines, refineries, and retail markets. Understanding the chain clarifies where disruptions are most likely to occur.Shows why companies specialize

Many firms focus on one segment to manage capital intensity and risk. Pure-play upstream producers, pipeline operators, and refiners each follow different business models.Clarifies how pricing power shifts

Profitability moves along the chain depending on market conditions. No single segment dominates at all times.Highlights opportunities for returns and innovation

Technology, logistics optimization, and decarbonization initiatives create opportunities in every segment, but in different ways.

For example:

Upstream margins tend to increase when crude oil and gas prices rise, especially for low-cost producers.

Midstream companies often earn stable, fee-based revenue through long-term transportation and storage contracts.

Downstream margins depend on refinery utilization, crack spreads, fuel demand, and product mix.

How Global Trade Fits Into the Value Chain

Oil and gas value chains operate on a global scale.

Crude oil and refined products are traded internationally using tankers and terminal infrastructure.

Natural gas is increasingly traded across borders through LNG export and import facilities.

Global benchmarks such as Brent, WTI, and Henry Hub reflect regional supply-demand dynamics shaped by upstream production and midstream logistics.

Global trade links local production with international markets, increasing both opportunity and exposure to geopolitical risk.

What’s often overlooked:

Value-chain understanding also helps evaluate company resilience. Firms integrated across multiple segments can better manage price cycles than single-segment players.

Overall, understanding these dynamics provides a clearer, more realistic picture of how the global energy system functions, and where strategic advantages truly lie.

FAQs

What is the oil and gas value chain?

The oil and gas value chain describes how hydrocarbons move from underground reservoirs to end users. It includes upstream activities (exploration and production), midstream operations (transportation, storage, and processing), and downstream processes (refining, petrochemicals, and distribution). Each stage adds value and serves a distinct role.

Why is the upstream segment considered high risk and capital intensive?

Upstream operations require large upfront investments in seismic surveys, drilling, and well construction, with no guarantee of commercial success. Production costs, price volatility, geological uncertainty, and regulatory requirements make upstream the most financially risky segment of the value chain.

How do disruptions in one segment affect the entire value chain?

A disruption in any segment can affect all others. Drilling delays reduce supply, pipeline constraints limit market access, and refinery shutdowns tighten fuel availability. Because the segments are highly interconnected, operational or geopolitical issues can quickly impact prices, supply reliability, and energy markets globally.